As summer nears its’ inevitable end, when time passes much too fast, I find myself looking back on the photographs and video I created over the past two months. While I am fortunate to have traveled to beaches and barbecues, mountain vistas and open seas, my favorite work comes from the fireflies that inhabit my backyard. For a few short weeks in June and July my yard and the surrounding forest become a natural light show, competing with even the best Christmas or laser light display.

I do love fireflies. For many, myself included, there’s a bit of nostalgia that comes from observing their beautiful display of bioluminescence. The warm, late nights spent chasing them and putting some in a mason jar to watch them light up the glass microcosm was oh so fun. And then upon release you watched the blinking golden lights overhead. It was pure magic.

Table of Contents

What are Fireflies?

Fireflies or, in the more colloquial but affectionate vernacular, ‘lighten’ bugs’ are not a fly at all but rather a type of winged beetle. Over 2400 species of firefly have been identified on all continents except Antartica with most found in the Americas and Asia and usually in temperate and tropical environments.

However there are even species found in more arid climates. Each species of firefly has a unique flash pattern that is used in communication for breeding. Males mostly flash when flying while females respond by flashing appropriately when perched and stationary.

A few years ago I completed an assignment on synchronous fireflies (Photinus carolinus) which I contend is one of the world’s greatest wildlife displays. The sight of thousands of these insects lighting up was a hypnotic, almost drool inducing, experience. The males of the species have a most amazing courtship ritual where, as their common name suggests, they synchronize their flash patterns between 5-8 flashes at a time.

It is believed the males do this to ensure appropriate mating so the female recognizes that it is a member of her species, and not another firefly which could be predatory. Now imagine those 5-8 synchronized flashes multiplied by thousands of other synchronized flashes happening simultaneously. It is so incredible. The most famous population is found within the boundaries of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park where a lottery system has been implemented to manage the amount of people who want to experience the magic of these fireflies.

There are a few other populations known in other states such as Pennsylvania and South Carolina that do not get nearly as crowded as the Smokies, but their popularity is growing. If you have a chance to see them, do it.

Tips and Tricks to Document Fireflies

From that assignment I learned a few tips and tricks to document fireflies and then later I began experimenting with other techniques in my own backyard. Today I photograph fireflies with either one very long exposure or by stacking multiple 30 second exposures into one frame. I also, when I can, try to photograph fireflies with a macro lens. And for the last few years I have been having a blast filming my backyard display and experimenting with low shutter speeds.

The trickiest park of firefly photography is that they display at night beginning at the very edge of when twilight meets total darkness. Hand holding your camera and fast shutter speeds is not applicable in these situations. In fact you probably will not be photographing fireflies in the traditional sense, at least not at first.

These insects are too small and because their activity corresponds with night the opportunities to photograph the detail of actual fireflies is very limited even on the best day. What you are going to photograph is the yellow flash they emit. Using long exposures you will capture the behavior of bioluminescence, leaving the viewer to interpret the presence of fireflies in their mind. But just as in life it is in these scenes of yellow flashes that people most remember of fireflies, of dark summer nights in grassy fields that glow.

The Gear

You will need to use a stable tripod. In a pitch you could utilize anything a camera could be set upon (I have even used large rocks before!) but a tripod is required if you want to capture high quality firefly images. You will usually want to be in a location before darkness falls and have your camera already set on the tripod.

This makes its much easier when moving around. It is good idea to check out the area during the day to have an understanding of the terrain. The last thing you want is to twist your ankle in a depression because you could not see where you were going or, maybe worse, have you expensive camera take a hard plunge into the dirt because it was not stable ground.

Make sure to take a flashlight and/or head lamp with a set of fresh batteries when moving around the field or forest in the dark. Fireflies are very sensitive to artificial light. In fact this is one of the major conservation issues facing the species.

Artificial light can negatively impact the lighting display of the males and in areas with high light pollution it has resulted in a disappearance of the lovable bugs. What you can do is wrap your flashlight with red (or blue) cellophane or connect a red light filter and turn your headlamp to its red light mode (most headlamps have this). The red light does not disturb the fireflies.

You want to avoid using the white light as much as possible, only when walking to a viewing area. Once at the viewing area use the red mode or cellophane to assist with moving around safely and setting up your camera. Always point your light source to the ground and do not use your cell phone as a light source or camera. This isn’t a concert after all.

Exposure

When taking long exposure photographs of fireflies there are two ways you can do this. Either with one very long exposure at a time (think a couple minutes or more) or by taking multiple 30 second exposures and then “stacking” them in post processing software.

On assignment I opted for the very long exposures. I experimented with exposures from two minutes upward to 25 minutes. The photograph illustrates this in the form of a five minute exposure with each yellow flash being recorded. Synchronous fireflies are found in dark forest with eastern hemlock and beech trees. In this area it was so dark that I could not get any detail of the forest with 30 second exposures.

So I used the moon as my light source. On this night the light of the full moon filtered through the canopy which illuminated the ferns and trees in the foreground. I would not have done this if I had not been in a very dark forest because photographing elsewhere, like a grassy field, in the full moon would not have worked. The light of the full moon is so strong that long exposures often result in looking like they were photographed during the day time which will obscure any firefly flash.

With all long exposure photographs your camera is susceptible to any shaking movement. The result being a fuzzy or soft photograph. I use an external shutter release cable for some of my cameras and for others I set the camera to a three or ten second delay before the shutter opens. This allows the camera shutter to open without any shake that could come from having your hand on the camera.

With 30 second exposures you can easily perform a quality check to confirm if there was any camera shake by looking at the image on your camera’s LCD screen and try again. For very long exposures, say an hour or more, if there was camera shake you will have lost that hour and have nothing to show for it. So always take a few 30 second exposures first and check the quality.

Lens Angles

In this photograph I opted to use a wide angle lens. The reason for this is because the fireflies were very close to the camera and I wanted to capture as much of the environment as I could. In other situations, such as the trees in my backyard or in meadows, I actually use short telephoto lenses.

Usually 100mm or 200mm focal length. If the fireflies are not close I will not be able to convey the beauty of their flash with a wide angle lens. The telephoto will compress a scene making one feel as if they were close to the flashes if the animals are slightly distant.

The stacking method involves taking multiple exposures and then using software, such as Photoshop, to blend them on top of one another. Many of the firefly photographs you have seen were probably made this way. Keeping the camera steady on the tripod is key here so that the software will properly stack the environment.

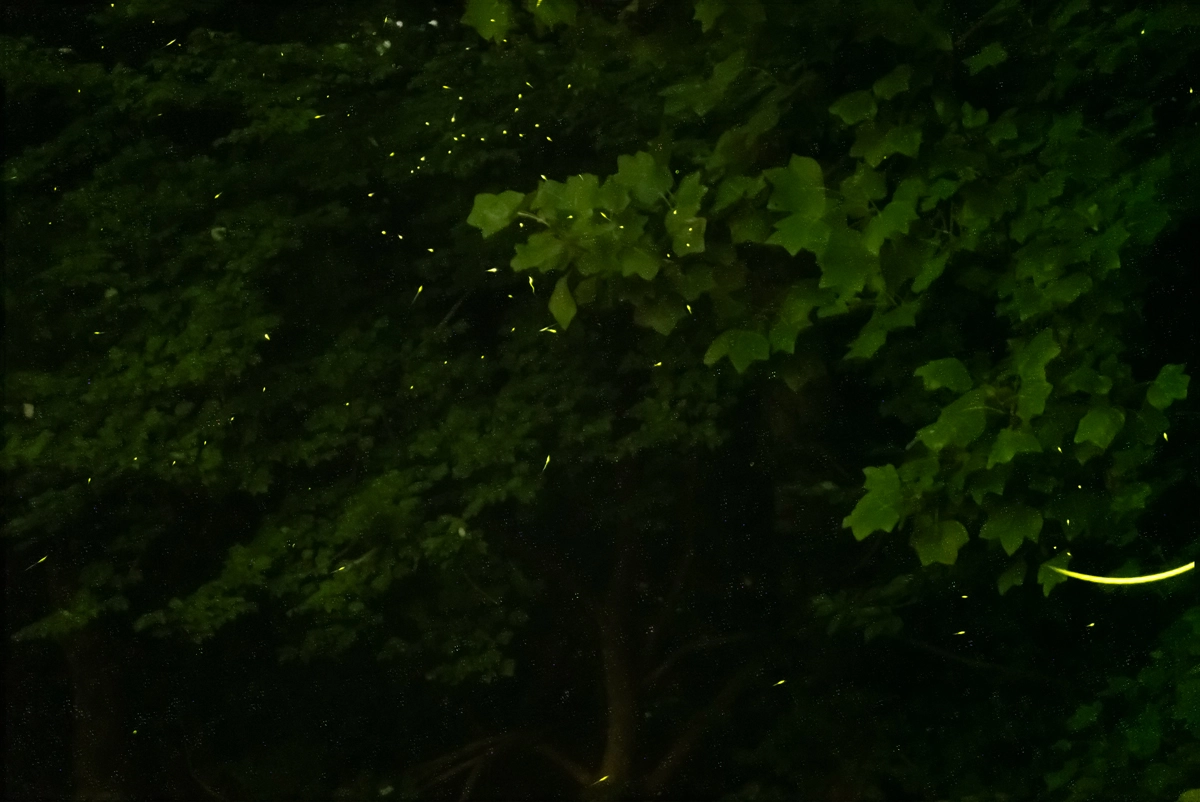

This is when an external shutter release cable is nice to have. I don’t want the slightest movement of my hand to move the camera every time I touch it. In the corresponding series you can see one photograph of the fireflies that display in the canopy of my backyard forest.

There’s a few flashes in there but not many. So I took five 30 second exposures (seen stitched together) and then I stacked them in Photoshop on top of one another and blended the layers together resulting in the final photograph showcasing all the flashes recorded over two and a half minutes.

Camera Settings

Regarding settings I set my camera lens at its widest aperture, usually f/2.8 or f/4, to let in as much light as possible in the darkness. Depending on the light from the moon, and whether I am standing in a forest or a meadow, my ISO can range from 200 to 3200.

You need to make sure your camera sensor is sensitive enough to capture those yellow flashes. Play around with your ISO to see what works best. Like most nature photography your first couple photographs will be more for figuring out what settings will work for you.

My most challenging firefly photographs are close up portraits using a macro lens. This is only possible when there’s still a bit of light left on the landscape. You will need of course a tripod, a macro lens (or at least a lens that focuses close), and, the most difficult part, finding a cooperative firefly that is perched.

It took me a few nights of watching where the fireflies were during evening and twilight and I looked for any flashes coming from shrubs and blades of glass. When I found a firefly I placed my tripod as close I could without disturbing it and focused manually.

Autofocus is going to fail in the very low light so manual focusing is a necessity. I keep the shutter speed around at between 1/15 to 1/30th of a second and push my ISO as high as I need to and the lens aperture set to its widest. These shutter speeds are not fast enough to freeze action so I usually have my trusty external shutter trigger attached and fire as many frames as I can to capture the flash.

The fireflies will move or, as soon as you get them in focus, fly away so you really want to be familiar with your tripod and camera/lens combo so you move rapidly when you need to. It is difficult and my success rate is low but when I find a cooperative firefly it is great fun to take their portrait as I would a friend!

Filming Fireflies

For the past three summers I have also filmed my backyard fireflies. And just like with still photographs, filming fireflies presents its own challenges and is a topic for another article. Because of these challenges though I have found myself experimenting more than I normally would. I film fireflies as soon as they begin flashing when there is still enough light to easily shoot at the standard 24 frames per second(fps).

I love the cinema look that comes from shooting at 24 fps and it is still the gold standard in movie production. Regardless of frame rate professional filmmakers follow the 180 degree shutter rule to create cinematic motion blur in their footage. It’s an easy rule to remember; set your shutter speed to as close to double the frame rate as possible.

At 120fps that means a shutter speed of 1/250th a second, for 30fps set your shutter to 1/60th a second and for 24 fps set your shutter to 1/50th of a second (as most cameras do not shoot at 1/48th a second). However when it gets to be very dark I find myself breaking that rule.

In this video I set my shutter speed to as low it could go for filming, a very slow 1/4th of a second. Now this would normally result in very choppy video but in the darkness I found that it allows for the flashes to really stand out in the footage. It has an almost timelapse quality to it which I think is pretty cool.

In Closing

In closing I look out into my backyard. My fireflies are gone and I will not see the next generation for many months. I find myself a little melancholy when their display goes dormant for another year but like every season, they will return and I’ll be ready with camera (and tripod!) in hand for when they do.